COBBETT'S GRAMMAR

Authors: Cobbett, William

Categories: Language

Politics / Society Non-fictionYear: 1823

Publisher: John M. Cobbett, 183, Fleet Street

Pagination: 230

Dimensions: 19 x 11.5 cm

City: London

Document Type: Book

Language: English

Printer: B. Bensley, Bolt-court, Fleet-street, London (c. 1796-?)

Seller: M. Ogle, 9, Wilson Street

Introduction: 'TO | MR. JAMES PAUL COBBETT. | LETTER 1. | INTRODUCTION.'

Advertisements: 'MR. COBBETT'S PUBLICATIONS. | PUBLISHED BY | J. M. COBBETT, 183, FLEET STREET, LONDON.'

Marginalia: Front paste-down endpaper: name written in black ink and subsequently blotted out with black ink; front free endpaper: 'Robert B***sell' [in black ink]; title-page: name written in brownish ink and subsequently blotted out with black ink, name written underneath unintelligible [in brownish ink].

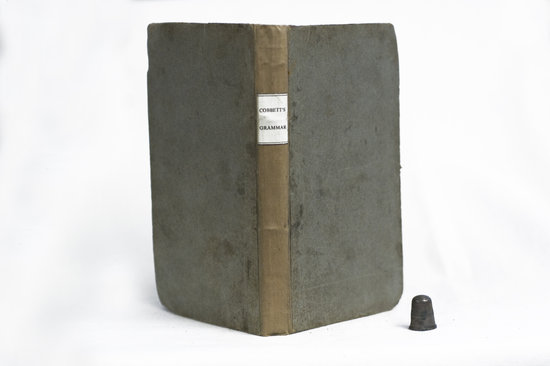

Binding: Light brown, quarter paper. Front and back covers light grey paper on board. SPINE: [black ink] 'COBBETT'S | GRAMMAR'.

Edges: Untrimmed

Notes:Full title: GRAMMAR | OF THE | ENGLISH LANGUAGE, | IN A SERIES OF LETTERS. | INTENDED FOR THE USE OF SCHOOLS AND OF YOUNG PER | SONS IN GENERAL; BUT MORE ESPECIALLY FOR THE USE OF | SOLDIERS, SAILORS, APPRENTICES, AND PLOUGH-BOYS. | TO WHICH ARE ADDED, | SIX LESSONS, INTENDED TO PREVENT STATESMEN FROM | USING FALSE GRAMMAR, AND FROM WRITING IN AN | AWKWARD MANNER. William Cobbett was born on March 9, 1763. His youth was spent working as a ploughboy and gardener. Although he attended school for a brief period, the majority of his education was completed at home under the supervision of his father. In 1783 he attempted to enlist in the Royal Navy but ended up in the West Norfolk 54th foot marching regiment. Cobbett was initially stationed at Chatham, but relocated to New Brunswick in 1785. He became a clerk to his regiment and quickly rose from the rank of corporal to sergeant major. Cobbett returned to England with his wife after his military discharge in 1791. His experiences in the military led him to write The Soldier's Friend, an indictment of the harsh treatment and poor pay of the common soldier. It was published in 1792. The same year he launched a court martial against several officers he suspected of peculation. He and his wife were forced to flee to France for six months when the court martial threatened to rebound on Cobbett. From France they moved to America, where they remained from 1792-1800. Cobbett continued his literary endeavors in America. He spent the first few years tutoring French emigres in English, and in 1794 wrote a pamphlet denouncing scientist and democrat Dr. Joseph Priestly. Over the next five years he wrote various pamphlets and articles under the pen name Peter Porcupine, making a name for himself as an anti-Jacobin polemicist. Cobbett's condemnation of the French Revolution and other manifestations of democratic and republican thought earned the favor of the British government, and he was immediately offered control over a government controlled newspaper upon his return to Britain. He declined the offer in order to launch his own daily newspaper. The Porcupine launched on October 30, 1800; however, lack of public interest forced Cobbett to pull out of the paper in 1801. Within a few months he was back, this time with a periodical. The Political Register was a success; it was published every week between January 1802 and Cobbett's death in 1835. In addition to his periodical, Cobbett was involved with the editing and publishing of Cobbett's Complete of State Trials and from 1804-1812 was active in collecting and printing parliamentary debates from the Norman Conquest onwards. However, due to financial difficulties, he sold his shares in both projects in 1812. In 1804, Cobbett's political sympathies and beliefs began to change and evolve. He began questioning the financial and political policies of William Pitt's administration, noting the growing animosity and disparity between those who paid taxes and those who did not. He also became increasingly concerned with rural England and the economic hardships of farm workers. His increased awareness of rural England's economic situation undoubtedly resulted from his move to Botley in Hampshire, where he purchased a farm and resided from 1805-1817. In 1807, Cobbett supported campaigners for parliamentary reform. His involvement in the reform movement eventually had personal repercussions. Acute hunger and unemployment plagued the British countryside in 1815 and 1816, resulting from the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and a disasterous grain harvest in 1816. Cobbett used his periodical to urge English workers to pursue parliamentary reform using non-violent means. His message was wildly popular and caught the attention of the British government, who responded in early 1817 by rushing several acts through parliament to reverse the growth of support for parliamentary reform. Fearing legal repercussions, Cobbett fled to America in 1817. He wrote two notable books during his two-year self-imposed exile: A Year's Residence in the United States of America (1818) and Grammar of the English Language, the latter which was used in English schools well into the 1930s. His return to England in 1819 was not easy, but his fortunes improved in the latter half of the 1820s. He lost his farm and went bankrupt in 1819. The Register, however, experienced increased circulation due to his involvement with the Queen Caroline affair and soon he began a four acre seed farm in Kensington. Cobbett also published the successful Cottage Economy in 1821, and undertook a series of rural rides between 1821 and 1826 that resulted in the publication of Rural Rides in 1830. He was able to expand his farming interests to an eighty acre farm at Barn Elms in 1830. His national reputation was greatly enhanced in 1831 after being put on trial by Lord Grey's government for ostensibly inciting rural workers to commit acts of violence and incendiarism. Cobbett conducted his own defense and was acquitted to the delight of his public. He used his political momentum to agitate for the Reform Bill of 1832 and ran a successful campaign for the two seats representing the new parliamentary borough of Oldham. He died on June 18, 1835 at his new 130 acre farm in Normandy, survived by his wife, three daughters, and four sons. John Morgan Cobbett was a bookseller, publisher, and printer in London. His trades dates are 1821-1823. Maurice Ogle was a Glasgow bookseller. From 1797-1808 his business was located at 7 Wilson Street East. In 1808 he moved from 7 to 8 Wilson Street, where he remained until 1815. Ogle is listed as being located at 9 Wilson Street from 1817-1823. In 1825, his business' name was changed to M. Ogle, Bookseller and Stationer and was located at 17 and 19 Wilson Street. Ogle moved his business to 1 Royal Exchange Square in 1834. The business' name changed again in 1835 to Maurice Ogle & Son, and remained that way until 1862. Ogle sold tracts of the Glasgow Religious Tract Society and its successors. Summary: p. i title-page and publisher's imprint. p. iii 'DEDICATION. | TO HER MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY, | QUEEN CAROLINE.' p. v table of contents. p. vii 'INTRODUCTION.' p. 9-230 text. p. 230 printer's imprint. p. 231 advertisement. William Cobbett makes the purpose of his book clear in his dedication to Queen Caroline. The object of Cobbett's Grammar is to "lay a solid foundation of literary knowledge amongst the laboring classes of the community" and to "give practical effect to their natural genius." Cobbett goes on to state that Britain naturally will benefit from the education of the labouring classes. The nation will be strenthened by an educated working class as it is "the people"--not the aristocracy--that are "the pillars that support the throne." Cobbett's grammar is an educational book with a distinctly political purpose. Cobbett wants to educate the working class in order that they might be able to effectively use words and thus affect political change. The book consists of 24 letters. Cobbett addresses the letters to his son, and each letter comprises a different grammar lesson. This format gives the text a colloquial feel; Cobbett is very conscious of his working class readership and strives to produce an educational book that is clear and easy to read. He teaches his audience the basic principles of grammar, demonstrates how to implement these principles, and helps his readers retain the information by using teaching strategies such as repetition. The book ends with examples of bad writing; he analyzes their faults and shows how incorrect grammar can affect a text's meaning. Politics and instruction converge in this last section. His examples are transcripts of the King's speeches and letters by Lord Castleraegh, the Duke of Wellington, Marquis Wellesley, and the Bishop of Winchester, the peaker of the House, and the regent. Under the guise of instruction, Cobbett launches a critique of the government and its practices. Although he is strictly criticizing their grammar, his political message is clear: these politicians' incorrect use of grammar is reflective of their overall political deficiencies. As the nation's leaders, these men should at least have grammatically perfect correspondences. However, Cobbett gleefully points out the inconsistencies and deficiencies in their writing, and proclaims their speeches and letters to be messy, nonsensical, and obscure. He stops just short of calling these politicians idiotic based on the quality of their written work. Cobbett concludes his critique by asserting that the British populace should not have to unquestionally acquiese to men who cannot write a grammatically correct sentance. His book is written out of and argues the egalitarian belief that political judgement and talent is not restricted to the British upper class; working class men as are politically capable given the proper instruction and education. References: Isaac, Peter. "Bensley, Thomas (bap. 1759, d. 1835)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. | British Book Trade Index. University of Birmingham, 2009. http://www.bbti.bham.ac.uk