RELIGIOUS COURTSHIP

Authors: Defoe, Daniel

Categories: Religion

Conduct Non-fictionDate Details: No date specified. Thomas Kelly published an edition in 1813, and then again in 1824, so the book's publication date must be from either one of these years.

Publisher: Thomas Kelly, 17 Paternoster Row

Pagination: 311

Dimensions: 21.6 x 14 cm

Illustrations: Five plates. Frontispiece 'Negum met by his Master in the Garden'. Half-title 'W.M. Craig, del., W. Swift fe.' 56 'The Gentleman listening at the Cottage Door.' 88 'The Mothers admonition.' 128 'The Gentleman's introduction to the family.'

City: London

Document Type: Book

Language: English

Marginalia: Front paste-down endpaper [book-plate] 'Harriet Robinson | Lowestoft.' Front blank page 'from Mervyn(?) Jones(?) Grams(?) | Daniel Defoe | Craig/Swift engraved titlepage | 3.50 pounds' [in pencil].

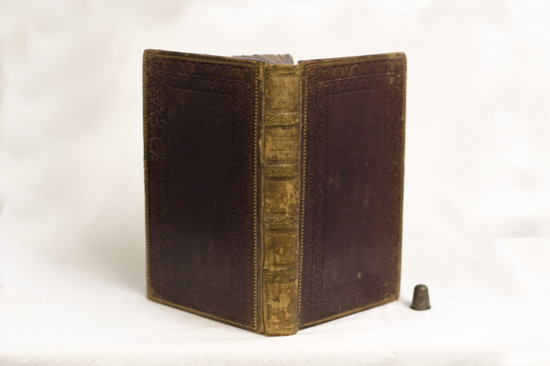

Binding: Full calf. Front and back covers blind/gilt-tooled. SPINE: [gilt-tooled] 'RELIGIOUS COURTSHIP'.

Edges: Trimmed

Notes:Full-title: RELIGIOUS COURTSHIP: BEING HISTORICAL DISCOURSES ON THE NECESSITY OF MARRYING RELIGIOUS HUSBANDS AND WIVES ONLY; AS ALSO OF HUSBANDS AND WIVES BEING OF THE SAME OPINIONS IN RELIGION WITH ONE ANOTHER. WITH AN APPENDIX SHEWING THE NECESSITY OF &C. Daniel Defoe was a businessman and writer. The year of his birth is speculated to be 1660, and he was born in or near London as the youngest child of a successful merchant. Defoe was educated at the Revd Charles Morton's dissenting academy in Newington Green. Although intended for the nonconformist ministry, he decided to pursue a career in trade. Defoe settled in Freeman's Yard, Cornhill, and quickly began a hosiery business. He married Mary Tuffley in 1684 and proceeded to have eight children, two of whom died before reaching adulthood. Defoe had an appetite for politics from early on and rapidly earned a reputation as a political agitator. He staunchly supported freedom of religion and the press, and was involved in various revolts from 1685-1687. The 1680s also saw him exanding his business interests. He opened a brick and pantile factory in Tilbury and began investing in ships and expanding into the import-export business. In the 1690s he started taking great financial risks, investing in highly speculative ventures such as civet cats and a diving bell. Defoe's investments did not yield him the returns he hoped for. He declared bankruptcy in 1692 for an astonishing 17,000 pounds and was committed to Fleet prison before being transferred to the king's bench prison on October 29, 1692. After a short release, he was recommitted on February 12, 1693 after more creditors demanded payment. His brick and pantile factory continued to operate, and he eventually also received employment as an accountant due to his association with men who were connected with King William. Around this time Defoe also began to write for money and submit his work to the government and private investors. He mainly wrote political pamphlets and poetry that supported King William and addressed social problems and political controversies. His most successful work from this period was the poem The True-Born Englishman, which went through fifty editions by the mid-eighteenth century. His agressive criticism of those opposed to religious tolerance landed him in jail for seditious libel in May 1702. Defoe was imprisoned in Newgate, where he was sentanced to be pilloried and imprisoned for an additional four months. His business suffered during his absence, and he was forced to declare backruptcy after he was released from prison. In 1704, Defoe drew on his writing skills and political interests to begin an innovative . . . There exists very little information on Thomas Kelly. He was a bookseller, printer, and publisher. His business is listed as being alternately located at 52 Paternoster Row, 53 Paternoster Row, 17 Paternoster Row, and 16 Paternoster Row. Kelly's company operated from 1809-1871. Summary: p. i half-title. p. ii title-page and publisher's imprint. p. iii 'PREFACE.' p. 7-251 text. p. 252-308 'RELIGIOUS COURTSHIP/THE APPENDIX.' p. 308-311 'HYMNS/For the Use of Masters of Families.' Religious Courtship is a domestic conduct book that addresses the complex issues women face when choosing their spouse. It specifically deals with the question of whether or not women should be concerned with their potential husband's religious beliefs (or lack thereof). Defoe's book emphasizes the importance of having a shared set of religious beliefs within a marital relationship, positing that a woman's spiritual and emotional well-being is dependent upon her husband's religious commitment. The text acts a guidebook for unmarried women, giving them both the arguments they can use to defend the importance of finding a husband who shares their religious beliefs, as well as the necessary questions they must ask and signs they must look for in order to reveal their potential spouses' religious faith or lack thereof. The book is divided into two parts. Part I consists of four dialogues, and part II consists of three dialogues. Defoe structures his conduct book as a narrative, rather than as a set of maxims. The narrative revolves around a family of three girls--all of marriageable age--and their father, who is well-meaning but somewhat unscrupulous. He prioritizes a man's wealth above his religious beliefs. Their mother has recently died and left her daughters with one injunction: they must marry religious men who share their faith. The eldest and the youngest take this injunction seriously, while the father and middle daughter place very little importance on the mother's final request. Part I primarily focuses on the courtship of the youngest daughter by a wealthy young man who she falls in love with, but who is not religious. After discovering his spiritual ambivalence, she determines to refuse him--much to the consternation of her father, who threatens to disown her. She is supported in her decision by her eldest sister and her aunt, who has recently lost her irreligious husband and is relieved to be free of his constant disrespect. The youngest daughter's beau is disturbed by her reason for refusing him and spends some time reflecting on his lack of religion. In this soul-searching state, he happens to overhear one of his poor tenants fervently praising God for his meager meal. Moved by his tenant's thankfulness, he is compelled to talk to him and discover the source of his joy and contentedness. His tenant soon leads him to God, and he becomes a serious Christian. Meanwhile, the youngest daughter has fallen into a state of grief over her father's ill treatment of her and the loss of her suitor; yet she remains steadfast in her decision. News of her suitor's conversion begins to filter in over time, but she remains unconvinced of its authenticity. After two years of seperation, they meet once more and she is assured of his spiritual transformation. Part I ends with their happy marriage. Part II follows the story of the middle daughter's courtship and marriage to an Italian merchant. Unlike her other sisters, the middle daughter takes the issue of her future husband's religion lightly. She is courted by a wealthy Italian merchant of her father's acquaintance. Her eldest sister fears that he is either an athiest or a Catholic; her father disregards the question of religion and approves his daughter's marriage on the basis of the merchant's wealth and courtly behavior. The middle daughter brushes aside her eldest sister's advice and listens to her father. After their marriage, it is revealed that he is, indeed, a devout Catholic. His wife is grieved and spends the eight years of their marriage trying to resist his religion. She does recount a scenario where he allows his black slave to choose which religion to follow (Catholicism or Protestantism) and where he states that fighting over religion is never constructive or good. However, he insists that his children be brought up Catholic and earnestly wishes for his wife's conversion. Although the middle daughter admits that her husband was consistently kind, his Catholicism distresses her so much that she is relieved when he dies after eight years of marriage. The narrative ends with the father expressing his regret for being ambivalent towards the religious committment of his son-in-laws, and admonishing all fathers to prevent their daughters from marrying men who either have no religion, or who do not share the same religion as their future spouse. The Appendix deals with the management of servants. The first dialogue is primarily between two servants-- Mary and Betty--although it begins with a conversation between Mary and her mistress. Mary is disgruntled that her mistress demands she attend church on the Sabbath. She complains to her fellow servant, Betty, and makes light of religion. Betty is a religious girl and is alarmed by Mary's sacriligious attitude. The narrative ends with Betty relating her discussion with Mary to her mistress, and Mary is promptly fired. The narrative moves into two dialogues between the Aunt, the eldest daughter, and the middle daughter regarding the importance of havbing religious servants. The middle daughter believes that it is essential that servants be of the same religion as thier masters and mistresses. The eldest daughter and Aunt are convinced that this is too rigid, and argue that it is better to have well-behaved religious servants than to demand that all servants adhere to the same religion as their masters and mistresses. They also discuss the issues surrounding the giving of characters. They agree that characters should be standardized in order to protect the employers and the employees. Former employees should be bound by law to give truthful accounts of ther former servants, and servants should not be denied a character and should have recourse to the law if thier employer give a malicious character. References: Backscheider, Paula R.‘Defoe, Daniel (1660?–1731).' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press: Sept 2004; online edn, Jan 2008.