Narrative

Gothic Chapbooks

1. At a time when books were considered a luxury item, chapbooks were a form of cheap print accessible to the lower classes. The chapbook was a flimsy paper-covered object of eight to thirty-two sheets (sometimes more), costing between one and six pence each. Most chapbooks did not include the author’s name or the publication date. They were one of many forms of street literature during the Romantic period, so called because it was sold on city streets, on country roads, in markets, and door to door, rather than in book shops. Chapbook sellers, known as chapmen, would travel from village to village peddling ribbons, needles, thread, and other small household objects, in addition to chapbooks.

Traditionally, chapbooks consisted of adventure or romance stories, collections of songs, texts on prophesy or fortune, popular science and health, almanacs, and advice books. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, they also included less expensive versions of fashionable or elite literary genres such as the gothic novel. Of course, the trend of supernatural elements in popular literature preceded the development of what we now describe as the gothic: for instance, long-established stories such as “Jack the Giant Killer” had been circulating in chapbook form since at least the mid-eighteenth century, and continued to do so after gothic narratives became popular.

Gothic chapbooks were often abridgements of popular novels or adaptations of melodramas and poems; others were loosely based imitations of longer texts or original stories. Although they did not have the space to examine characters’ emotional responses or thought processes in the way longer works did, gothic chapbooks did incorporate themes, settings, and motifs common to many gothic works. Settings tended to be geographically and temporally remote, often medieval or renaissance Italy, Spain, Germany, or France, and sometimes other, more exotic locations. More specifically, gothic texts in the romantic period were noted for the presence of castles, dungeons, towers, subterranean passages, trap doors, crypts, tombs, and other dark, mysterious spaces. They featured chilling scenes of suspense and terror, which might involve supernatural phenomena such as ghosts, demons, werewolves, or vampires, or the machinations of monstrous villains (in this period, usually men). Above all, gothic narratives employed suspense techniques to evoke pleasurable feelings of terror or horror in their readers, and to “transport” them into the fictional world of the narrative. This strange emotional blend of pleasure and terror is arguably the essence of the gothic genre.

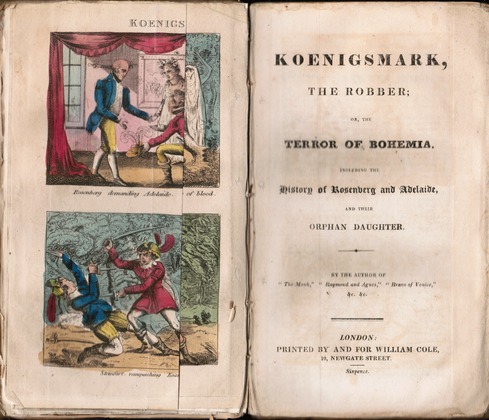

“Koenigsmark, the Robber; or, The Terror of Bohemia, Including the History of Rosenberg and Adelaide, and their Orphan Daughter,” by the author of “The Monk,” “Raymond and Agnes,” “Bravo of Venice,” &c. &c, is 22 pages long. Published and Printed by William Cole, London. Price sixpence. It includes a fold-out page of colour illustrations depicting various scenes in the story. This artifact is part of a collection of chapbooks bound together under the title Brochures Diverses.