THE GENUINE BOOK

Authors: Perceval, Spencer

Categories: Politics / Society

Conduct Non-fictionYear: 1813

Publisher: W. Lindsell, Wigmore Street

Pagination: 354

Dimensions: 21.5 x 13.5 cm

City: London

Document Type: Book

Language: English

Printer: R. Edwards, Crane Court, Fleet Street; M. Jones, 5, Newgate-Street

Seller: M. Jones, 5, Newgate-Street

Marginalia: Front paste-down endpaper [book-plate] 'James Dunlop | Tollcross.'

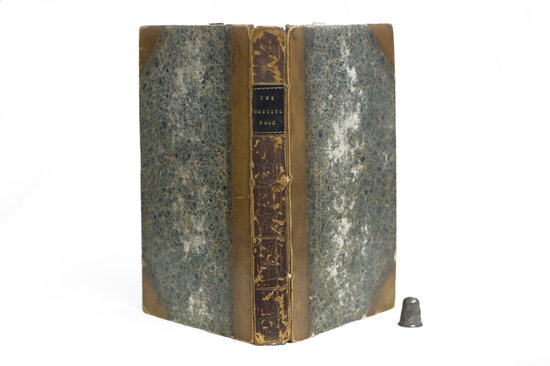

Binding: Half calf. Front and back covers marbled board. SPINE: [blind/gilt-tooled] 'The Genuine Book'.

Edges: Trimmed

Notes:Full-title: THE GENUINE BOOK AN INQUIRY, OR DELICATE INVESTIGATION INTO THE CONDUCT OF HER ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCESS OF WALES; BEFORE LORD ERSKINE, SPENCER, GRENVILLE, AND ELLENBOROUGH, THE FOUR SPECIAL COMMISSIONERS OF INQUIRY, &C. Spencer Perceval was born on November 1, 1762. He was the second son of John Perceval, second earl of Egmont, and his second wife, Catherine. Perceval began his education at Harrow School in 1774, and entered Trinity College at Cambridge in 1780. He was noted for his studiousness and was successful academically, taking his honory MA in 1782. He also became increasingly committed to Evangelical Anglicanism and began to associate with an influential group of evangelicals, a committment and association that shaped both his personal ideology and his career. Perceval decided to pursue law following his MA; he entered Lincoln's Inn in 1783 and was called to the bar three years later. In 1790 he held his first post as deputy recordership of Northhampton, followed by commissionership of bankrupts and the sinecure post of surveyor of the meltings and the clerk of the irons in 1791. Perceval's new financial stability allowed him to marry Jane Wilson in 1790 and begin a family that would eventually number six girls and six boys. His interest in politics became evident in 1791 and 1792 when he published two anonymous pamphlets. The first pamphlet argued in favor of continuing the impeachment of Warren Hastings, and the second pamphlet offered advice on how to resist radicalism. His censure of the French Revolution certainly helped him secure an appointment as Junior Counsel for the Crown at the trials of the radicals Thomas Paine and John Horne Tooke in 1792 and 1794, respectively. His star continued to rise: in 1794 he was made counsel to the Board of Admiralty and in 1796 he was made a KC and became a bencher at Lincoln's Inn. 1796 also marked the beginning of his career as a politician as he was elected to Parliament. Perceval quickly rose through the political ranks. In 1798 he was appointed Solicitor to the Ordinance, in 1799 he became Solicitor-General to the Queen, in 1801 he was appointed Solicitor-General, and in 1802 he became the Attorney General. He was the Pittite's leading law officer in the Commons from 1806-1807, memorably defending the Princess of Wales when she stood trial. He edited a book about the trial in 1807, entitled The Proceedings and Correspondence, upon the subject of the Inquiry into the Conduct of Her Royal Highness, The Princess of Wales. Its publication was suppressed until 1813, when it was reprinted as The Genuine Book. Perceval was a thorough Pittite and an excellent debator. He was aggressively opposed to Catholic emancipation and parliamentary reform and adamantly supportive of the war with France, abolition, and the regulation of child labour. Under the Duke of Portland's Pittitie ministry, Perceval was offered and eventually accepted the Chancellorship of the Exchequer and the Duchy of Lancaster in 1807. Following Portland's stroke in September of 1809, the Cabinet recommended Perceval to the King as the new Prime Minister. He accepted on October 2, taking on the difficult task of guiding his ministry through a politically unstable and tumultuous time. England was at war with France, the opposition groups together held more seats than Perceval's ministry, and his ministry lost the support of the Crown when the King lost his sanity and was temporarily replaced by his Whig-leaning son. Despite the issues facing his government, Perceval managed to build a strong ministry by the spring of 1812. However on May 11, 1812, Spencer Perceval was assassinated in the lobby of the House of Commons by John Bellingham, a merchant with a grudge against the British government. Bellingham was hanged, and a private funeral was held for Perceval on May 16. There is little information on William Lindsell, other than the fact that he was a publisher, bookseller, and stationer and operated a business in London between the years of 1794 and 1826. His business was known by three different names over the course of his career: Lindsell & Co. (1794-1801), William Lindsell (1802-1826), and Lindsell and Son (1826). The company's name is changed to Henry Lindsell in 1827, indicating William's departure from the business. Richard Edwards was a printer and publisher in London. Little is known about Edwards. According to Maurice J. Quinlan, "Richard Edwards . . . was an obscure individual, who is listed in the Post Office London Directory simply as a printer" (364). M. Jones is an equally obscure individual. Nothing is known about him other than the fact that he was a bookseller and printer in London. James Dunlop was a successful business man in Glasgow. He was born in 1742 to Colin Dunlop, a tobacco merchant who owned one of the great Virginia houses. James carried on his father's business until 1793, when a severe monetary crisis forced him to sell his company and his estates. However, he retained the rights to the minerals on one of his estates, and established himself as a coal master and owner of Clyde Iron Works. The business flourished under his control and in 1810 he bought the Tollcross estate. James died in 1816. He was succeeded by his son, Colin, who made his name as an active Whig politician. The Tollcross estate has withstood both numerous renovations and years of neglect and is presently a care home for the elderly. Summary: Title-page and publisher's imprint. p. i 'ADVERTISEMENT.' p. iii text contents. p. v appendix (a) contents. p. vii appendix (b) contents. p. 3-246 text. p. 1 appendix (a). p. 49 appendix (b). p. 109 'LIST OF THE DOCUMENTS STATED IN THE APPENDIXES.' The Genuine Book (commonly referred to as simply 'The Book' when it was first published) is a compilation of the documents used by the four commissioners in charge of the 1806 private investigation of Princess Caroline's alleged infidelity. The 'Advertisement' at the beginning of the book states the complete authenticity of the following account and assures its readers that it is an exact copy of the original suppressed book. The book then begins with the the report of the commissioners to King George III. The commissioners detail the allegations (that Princess Caroline had adulterous relationships with various men, that she gave birth to an illegitimate son in 1802, and that the boy she 'adopted' is her own), describe the evidence and name the informants, and finally state that after much deliberation, they have decided that there is no foundation to the allegations and that they believe the Princess to be innocent. The document is signed by Erskine, Spencer, Grenville, and Ellenborough and dated July 14, 1806. The report is followed by a series of letters exchanged among Princess Caroline, King George III, and the Lord Chancellor between the dates of August 12, 1806 and March 5, 1807. In Princess Caroline's first letters she asserts her innocence and demands official copies of all the depositions so that she might know precisely what she is being accused of, who her accusers are, and when the declarations were made. Having received these papers, she writes a lengthy letter to the King defending herself against all of the allegations. She addresses each of the circumstances described by the witnesses and systematically exposes the witnesses as perfidious or ignorant and their accounts as groundless or false. She questions the informants' motives and reliability and blames many of their allegations on misinterpretation or blatant fabrication. Caroline also emphasizes her foreignness and suggests that though her intentions be innocent, her behavior might sometimes be misinterpreted by the English. Following this letter of defense are the depositions of Thomas Manby, Thomas Edmeades, Jonathan Partridge, Philip Krackeler, and Robert Eaglestone--alternately vindicating and casting aspersion on the Princess' behavior--and the memorandum of the conversations that occured between Lord Moira, Mr. Lowten, and Mr. Edmeades. Another series of letters exchanged among Princess Caroline, King George III, and the Lord Chancellor commences after the depositions and memorandum. After waiting for nine weeks, Caroline writes to complain about the delay and presses the King for an immediate response to her defense. She argues that the longer the King waits to come to a decision, the more her public image suffers. A letter from the King quickly follows relating the judgement of the four commissioners in her favor. He validates her innocence and welcomes her back into his presence at a set time. However, he rescindes his offer in a later letter, citing resistance from Prince George--Caroline's husband. The Prince questions the commissioners' judgement and is demanding further investigation. Caroline responds by questioning the King's sudden doubt given his previous affirmation and emphasizes the unjust nature of the Prince's interposition. She again calls attention to the damaging affect the King's indecision and silence has on her public image, and requests that she be restored to the use of her apartments, or at least given quarters closer to Court than her current retreat. Her demand is given in conjunction with a threat: if the King does not respond to her request within a week, she will publish the investigation's proceedings to the world so that the public might know her innocence. Caroline also transcribes a letter she received from the Prince after the birth of their daughter in which he states his disdain for her and his disinterest in their marriage; she further transcribes her response, in which she states her devotion to him and their marriage. The letters emphasize her point that her husband has treated her unjustly. She also argues that removal from the Prince's protection has exposed her to ruinous gossip. Caroline insinuates that the Prince's behavior towards her is partially to blame for the allegations currently leveled against her. Her final letter to the King, written a little over a week after her last one, states her decision to carry through with her threat and publish the papers used in the investigation. The first edition of this book was published anonymously in 1807, under the title The Proceedings and Correspondence, upon the subject of the Inquiry into the Conduct of Her Royal Highness, The Princess of Wales. This edition was suppressed, but the book was reprinted in 1813 with Perceval as the acknowledged author. For more information on the 'Delicate Investigation,' visit http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caroline_of_Brunswick References: Jupp, P. J. "Perceval, Spencer (1762–1812)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press: Sept 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/21916]. | # Memoir of William Cowper # Maurice J. Quinlan and William Cowper # Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 97, No. 4 (Sep. 28, 1953), pp. 359-382 | Maxsted, Ian. Exeter Working Papers in Book History. [http://bookhistory.blogspot.com/2007/01/london-1775-1800-l.html]. June 1, 2001.