TALES OF MY LANDLORD, SECOND SERIES

Authors: Scott, Walter

Categories: Fiction

History Romance Prose NovelYear: 1818

Month: July

Day: 25

Publisher: Archibald Constable and Company

Pagination: V.I 333 ; V.II 322 ; V.III 328 ; V.IV 375

Dimensions: 17.5 x 11 cm

City: Edinburgh

Document Type: Book

Edition: First

Language: English

Printer: James Ballantyne and Co.

Seller: Various

Price: £1.12.0

Introduction: 'TO THE BEST OF PATRONS, | A PLEASED AND INDULGENT READER, | JEDIDIAH CLEISHBOTHAM | WISHES HEALTH, AND INCREASE, AND CONTENTMENT.'

Advertisements: V.I page between half-title and title-page 'This day were published, | IN ONE VOLUME, |CRIMINAL TRIALS, | ILLUSTRATIVE OF THE TALE ENTITLED "THE HEART | OF MID-LOTHIAN"' (A historical account of the Porteous riots 1736, one of the key events in Scottish history upon which the novel is based).

Marginalia: V.I front free endpaper, pricing (in pencil); V.I, II, III, IV front free endpaper blank verso, unidentifiable signature (blue ink).

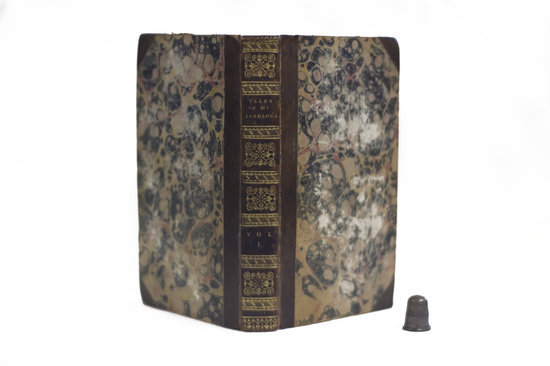

Binding: Brown, half calf. Front and back covers marbled board. SPINE: [gilt-tooled] '(decorative device) | TALES | OF MY | LANDLORD | (decorative device) | (decorative device) | VOL. | I. | (decorative device)'.

Edges: Trimmed

Notes: Other title: The Heart of Mid-Lothian

Notes:Full-title: TALES OF MY LANDLORD, SECOND SERIES, COLLECTED AND ARRANGED BY JEDEDIAH CLEISHBOTHAM, SCHOOLMASTER AND PARISH-CLERK OF GANDERCLEUGH. IN FOUR VOLUMES. Much has been written about the life of Sir Walter Scott. The following compilation provides a basic outline. Refer to the reference section for further information. Scott, Sir Walter (1771–1832), poet and novelist, was born in College Wynd in the Old Town of Edinburgh on 15 August 1771, the tenth child of Walter Scott (1729–1799) and Anne Rutherford (1739?–1819). His father, son of Robert Scott (1699–1775), a prosperous border sheep farmer, and of Barbara Haliburton, became a writer to the signet in 1755, and had a successful career as a solicitor in Edinburgh. His mother was the daughter of Dr John Rutherford (1695–1779), professor of physiology in the University of Edinburgh, who had studied in Edinburgh, Rheims, and Leiden (under Boerhaave), and of his first wife, Jean Swinton. Scott's parents married in 1758, and had thirteen children: besides Walter, those who survived childhood were Robert (1767–1787), John (1769–1816), Anne (1772–1801), Thomas (1774–1823), and Daniel (1776?–1806)" (“Scott, Sir Walter” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). Timeline • 1773 - Contracts polio which renders him lame in his right leg for the rest of his life. Sent to live with his grandfather Robert Scott at Sandyknowe in the Borders. • 1775 - Briefly returns to Edinburgh following his grandfather's death but is sent to Bath in the summer to attempt a water cure. Visits London. • 1776 - Returns from Bath in the summer and is sent back to Sandyknowe. • 1778 - Returns to Edinburgh to live at his father's new house at 25 George Square. • 1779 - Enters the High School of Edinburgh. • 1783 - Leaves school and goes to Kelso to stay with his Aunt Janet (Jenny) Scott for a year. At Kelso Grammar School, meets his future friend and business partner, James Ballantyne. • 1783-86 - Attends Edinburgh University. • 1784-85 - Health deteriorates again and has to interrupt his studies. All treatments fail and is sent back to Kelso to live with his aunt for a year. • 1786 - Apprenticed to his father's legal firm, but soon decides to aim for the Bar. • 1786-7 - Visits the Highlands on business where he meets a client of his father, Alexander Stewart of Invernahyle, who had once fought a duel with Rob Roy MacGregor. Scott, only fifteen years of age, also meets Robert Burns. This remains the only meeting of the two great Scottish writers. • 1789-92 - Resumes his studies and reads law at Edinburgh University. • 1790 - Meets and falls in love with Williamina Belsches. • 1792 - Qualifies as a lawyer and is admitted to the Faculty of Advocates. • 1792-6 - Practises as an Advocate in Edinburgh. • 1797 - Heartbroken when spurned by Williamina who marries William Forbes of Pitsligo. Visits the Lake District and meets Charlotte Carpentier whom he marries on Christmas Eve in Carlisle Cathedral. Moves to rented accomodation in George Street, Edinburgh. • 1798 - Rents a cottage at Lasswade on the River Esk, where he will summer each year until 1804. • 1799 - Scott's father dies in April. Birth of Scott's first daughter, Charlotte Sophia, on 24 October. On 16 December, Scott becomes Sheriff-Deputy of Selkirkshire, an office he holds until his death in 1832. • 1801 - Birth of Scott's first son, Walter, on 28 October. In December, moves to 39 Castle Street which will remain his Edinburgh home until 1826. • 1803 - Birth of Scott's second daughter, Anne, on 2 February. • 1804 - Moves with his family to Ashestiel near Galashiels, retaining 39 Castle Street as as a winter residence. • 1805 - Enters into a secret business partnership with James Ballantyne. Birth of Scott's second son, Charles, on 24 December. • 1806 - Becomes Principal Clerk to the Court of Session in Edinburgh, permitting him a steady income from the law without having to practise as an Advocate. • 1809 - Becomes half-owner of John Ballantyne's publishing company. • 1810 - Williamina Forbes dies at the age of 34. • 1811 - Buys Cartley (nicknamed Clarty) Hole Farm. Extends the original four-room cottage and renames his new home Abbotsford. Scott and his family move into Abbotsford in 1812. • 1813 - Collapse of John Ballantyne and Co. The company's assets are bought by Archbald Constable and Co. who remain Scott's publishers until 1826. Scott is rescued from impending bankruptcy by his patron, the Duke of Buccleuch (see Financial Hardship). • 1816 - Inherits the fortune of his brother, Major Scott. • 1818 - Accepts a baronetcy. • 1819 - Scott's mother dies. • 1820 - Elected President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. • 1822 - Plays a leading role in organizing the visit of King George IV to Edinburgh. This is the first visit of a Hanoverian monarch to Scotland. • 1825 - Scott's eldest daughter Sophia marries John Gibson Lockhart, his future biographer. In November, Scott starts his famous journal. Suffers from gallstones and fears financial ruin. • 1826 - Becomes insolvent after the failure of his publishers, Archibald Constable, and his printers, James Ballantyne (see Financial Hardship). Pledges the future income from his publications to a trust in order to repay his creditors. The start of an excessive period of work, which is to affect his health. On 15 May, Scott's wife dies. • 1827 - Finally admits to the authorship of the Waverley novels at a public dinner. • 1828 - Makes preparations for a complete annotated edition of his works, later named the Magnum Opus. • 1829 - Suffers from haemorrhages. • 1830 - Declines the offer of a Civil List pension and the rank of Privy Councillor. • 1831 - Suffers a stroke and then apoplectic paralysis. Goes to Italy with Lockhart to recuperate. On 15 December receives news of the death of his ten year old grandson Johnnie Lockhart. • 1832 - Returns from the continent. Dies at Abbotsford on 21 September and is buried beside his wife in Dryburgh Abbey. The Poet • 1782 - Writes his earliest verse. • 1796 - Publishes The Chase, and William and Helen, translations of two poems by Gottfried August Bürger. • 1797 - Translates dramas from the German of Maier, Iffland, Schiller, and Von Babo, and ballads and drama by Goethe. • 1799 - Publishes a translation of Goethe's drama Goetz von Berlichingen. The Ballantyne Press privately prints Scott's ballad 'The Eve of St John' and An Apology for Tales of Terror, containing three of Scott's translations from German. • 1800 - Collects, edits and reworks material for a ballad collection called the Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border to be published by Ballantyne. Matthew Gregory Lewis's anthology Tales of Wonder contains three original ballads by Scott. • 1802 - First edition of the Minstrelsy. • 1803 - An expanded 3 volume edition of the Minstrelsy is published. • 1804 - Scott's edition of the medieval romance Sir Tristrem with a conclusion furnished by himself. • 1805 - The Lay of the Last Minstrel is published to critical and popular acclaim. • 1807 - The Edinburgh Publisher Archibald Constable pays Scott 1,000 guineas for a poem he had not yet written: Marmion went on to sell 28,000 copies by 1811. Completes Joseph Strutt's historical romance Queenhoo Hall. • 1809 - Involved in the foundation of the Quarterly, a Tory rival to the Edinburgh Review. • 1810 - The Lady of the Lake is published and proves even more popular than Marmion, selling 25,000 copies in eight months. • 1811 - Publishes The Vision of Don Roderick. • 1812 - Has a new poetic rival in Lord Byron, whom he meets in 1813. • 1813 - Rokeby and The Bridal of Triermain are published. Is offered and declines the Poet Laureateship. The Novelist • 1814 - First novel Waverley published anonymously. Becomes the most successful novel ever published in English. • 1815 - Publishes second novel Guy Mannering and The Lord of the Isles, his last major poetic work. During a trip to Waterloo and Paris, writes The Field of Waterloo. • 1816 - The Antiquary and the first series of Tales of My Landlord are published, consisting of Old Mortality and The Black Dwarf. Also publishes Paul's Letters to His Kinsfolk, imaginary letters describing his travels in Belgium and France. • 1817 - Writes Rob Roy and publishes Harold the Dauntless, his last long poem. • 1818 - The Second Series of Tales of My Landlord (The Heart of Midlothian) is published. Writes 'Essay on Chivalry' for the Encylopaedia Britannica. • 1819 - Suffering from gallstones, dictates A Legend of Montrose and The Bride of Lammermoor which are later published as Tales of My Landlord, Third Series. Also dictates Ivanhoe which is published at the end of the year and is enormously successful, selling 10,000 copies in a fortnight. • 1820 - The Monastery and The Abbot are published. • 1821 - Kenilworth and The Pirate are published. • 1822 - The Fortunes of Nigel is published. • 1823 - Peveril of the Peak, Quentin Durward and St. Ronan's Well are published. • 1824 - Redgauntlet is published. • 1825 - Tales of the Crusaders, The Betrothed and The Talisman are published. • 1826 - Leads a successful campaign through The Letters of Malachi Malagrowther to preserve the Scottish banknote. Publication of Woodstock. • 1827 - The Life of Napoleon and Chronicles of the Canongate are published. • 1828 - The Fair Maid of Perth and the First Series of Tales of a Grandfather are published. • 1829 - Anne of Geierstein and the Second Series of Tales of a Grandfather are published. • 1830 - Writes, at J.G. Lockhart's suggestion, the Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft. Third Series of Tales of a Grandfather. • 1831 - Fourth Series of Tales of a Grandfather and Fourth Series of Tales of My Landlord (Count Robert of Paris and Castle Dangerous) are published. Summary Scott was a collector, translator, editor, critic, poet, and novelist. He was the most famous English romantic poet in Britain and Europe, and remained popular despite the rise of Byron and others, before becoming the leading novelist across the Continent and in America throughout the nineteenth century. His influence as collector and critic, but especially as poet and novelist, at home and abroad, was immense. The Waverley novels in particular influenced others such as James Fenimore Cooper, Alessandro Manzoni, Honore de Balzac, and many others, both recognized and unrecognized, who played significant literary, social, and political roles in the revolutionary period relative to their respective spheres of influence. Archibald Constable (1774–1827), bookseller, stationer and publisher, was born in the parish of Carnbee near Anstruther in Fife on 24 February 1774, one of the seven children of Thomas Constable (1736–1791) and Elizabeth Myles (1733–1819). The Scottish Book Trade Index provides a succinct account of his career: “Apprenticed to Peter Hill bookseller, Edinburgh for six years 2 February 1788 - January 1794. Agreed to remain with Peter Hill as shopman for one year more. Married Mary Willison, daughter of David Willison, printer in Edinburgh, 16 January 1795. Member of the Edinburgh Bookseller's Society 4 April 1796. In 1804 he took Alexander Gibson Hunter into partnership and the firm became Archibald Constable & Co. Gibson Hunter retired from the partnership in 1811 to manage his estate which he had inherited on the death of his father in the previous year. Constable then entered into partnership with Robert Cathcart. At Cathcart’s request his brother-in-law Robert Cadell was included in the partnership, which was to last for ten years. Robert Cathcart however died 18 November 1812. Constable’s wife died 28 October 1814. Robert Cadell married Constable’s eldest daughter on 14 October 1817. She died on 16 July 1818. Cadell remained with the firm until the crash of 1826. On the 12 February 1818, Constable remarried: his wife being Charlotte, daughter of the late John Neale. As a direct result of the bankruptcy of Constable’s London agents Hurst, Robinson, and a long-term effect of the system of discounted bills set up in 1814 to prevent the immediate bankruptcy of Ballantyne & Co the firm of Archibald Constable & Co stopped payment on 19 January 1826. Archibald Constable and Robert Cadell went their separate ways, Scott choosing to stay with Cadell. The company went into receivership, but Constable had the comfort of seeing his Miscellany published and a great success. Constable died on 21 July 1827. The National Library of Scotland has sale catalogues of 1799, 1801 and 1808 and that of the sequestrated estate. Archibald Fyfe of Constable & Co 1820; H.S.Constable of Constable & Co 1830. Archibald Constable died 21 July 1827. Archibald Constable’s correspondence and that of the firm is in the National Library of Scotland (MSS 319-334; 668-684; 789-92 etc.).” The following list of business locations is also useful: At the Cross 1794-98; Opposite the Cross Well, North Side 1799-1804; Archibald Constable & Co. same address 1804-10; 255 High St 1811-22; 10-11 Princes St 1823; 10 Princes Street 1824-27; 17 Waterloo Place 1828; 19 Waterloo Place 1829-31. Jane Millgate describes Archibald Constable’s early fight against the imperialism of the London trade and his desire to protect and expand the literary productions of Scotland (“Constable” 112). But as Constable and Scott knew, London was essential to success in the British book trade as the bulk of all publications went to London. Appropriately for Scott, although a Scottish nationalist “[Constable] aimed at a dominant position in British publishing, and in mounting a campaign to that end he had major assets on his side: gifted authors; an alertness to new intellectual, social, and economic developments; energy and imagination in publicizing and selling his wares; and a soaring confidence” (Millgate, “Constable”113). Early on, Constable struck a deal with the London publisher Longman. This gave Constable much-needed financial support and access to the London market. This relationship eventually broke down in 1806, but was later re-established by 1814 after other arrangements did not work out. Under financial duress due to his taking on the Encyclaepedia Britannica, Constable was forced to turn to Robinson, partly for financial support and partly because he was able to move vast quantities of stock, in Britain and America. “As a reward for the vigorous pursuit of such American sales, Robinson succeeded in extracting from Constable proofs or early copies of popular publications that could be profitably transmitted to America for sale to publishers eager to win the race for American copyright – works by the Author of Waverley being, of course, especially prized” (Millgate, “Constable” 118). Millgate writes that Rob Roy appears to be the first Waverley novel to follow this route (“Constable” 119). This occurred January 1818 and Rob Roy was followed by The Heart of Mid-Lothian in July of the same year. Also of interest: “In negotiating with publishers, Scott employed John Ballantyne [James’s brother] until his death in 1821 as his literary agent, but as John was not trusted James would sometimes substitute for him. Scott was the first writer to have an agent, and used him to play one publisher off against another. In 1817 he instructed James to negotiate a deal for Tales of my Landlord with the Edinburgh publisher William Blackwood and his London correspondent John Murray instead of the usual Constable. Scott preferred Constable to all other publishers, but by trying another publisher he created an auction for his work. What Scott achieved by such manoeuvres was not an increase in the author's profits, but more contracts for as yet unwritten works, which were paid for by promissory bills payable at stated intervals in the future. The publisher expected to be able to pay these as the cash came in from the sales of the work, while Scott usually took them to the bank and sold them for ready money at a discount on their face value. The publisher then owed the money to the bank, not the author” (Hewitt, “Scott, Sir Walter” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). James Ballantyne (1772–1833), “printer and newspaper editor, was born at Kelso, Roxburghshire, Scotland, on 15 January 1772, the eldest child of John Ballantyne (1743–1817), general merchant, and Jean (1745?–1818), daughter of James Barclay, rector of Dalkeith high school, and his wife, Elizabeth” (Ragaz, “Ballantyne, James” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). He attended school at Kelso with Walter Scott. Before entering an apprenticeship with a solicitor in Kelso, he passed the winter of 1786-87 at Edinburgh University. In 1795 he started in business as a solicitor at Kelso, and also undertook the printing and editing of a newspaper, the Kelso Mail (Mail Office Bridge Street Kelso 1797-1802). In 1799 he printed Scott’s Apologies for some tales of terror and The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802-3). On Scott’s suggestion he moved to Edinburgh in 1802 and set up his press with a loan of £500 from Scott (Border Press, Holyrood House 1802-03). In 1805 Ballanytne lacked the capital to undertake all the work offered. Scott advanced £500 more and took a one-third share in the business (Foulis Close Edinburgh 1804-05; Ballantyne & Co, Paul’s Work, North back of the Canongate 1806-30). “In 1808 John Ballantyne & Co booksellers was launched, superintended by James’s younger brother John. Scott put up half the capital and the brothers, James and John a quarter each” (Scottish Book Trade Index). The publishing business failed. But James’s printing firm was successful. In 1826, however, the firm became involved in Archibald Constable’s bankruptcy. One of the unique aspects of studying Scott is his intimate relation to printer and publisher. In The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period William St. Clair writes: “For a time, Scott and his partners achieved an ownership of the whole literary production and distribution process from author to reader, controlling or influencing the initial choice of subjects, the writing of the texts, the editing, the publishing, and the printing of the books, the reviewing in the local press, the adaptations for the theatre, and the putting on of the theatrical adaptations at the theatre in Edinburgh which Scott also owned” (170). Jane Millgate writes specifically of the reciprocity of the relationship between the printer/publisher James Ballantyne and Walter Scott (“Kelso” 33). She describes a sympathetic professional cooperation (Millgate, “Kelso” 40) that gave Scott authorial and editorial control of the entire publishing process while providing Ballantyne with much needed literary material necessary to achieve his aesthetic and professional objectives. Further, Ballantyne had the sort of literary sensibility and care for craftsmanship that enabled Scott to trust serialized or completed works to his press. Millgate notes discussions concerning paper quality, ink, typeface, format and size, layout, and font sizes. Also, prior to the beginning of their printer/author relationship, Ballantyne already had put plans in motion to extend his contacts from Kelso to London. He had also shown interest in producing a typography that was first-rate by purchasing equipment from Glasgow. With Scott’s encouragement, Ballantyne moved to Edinburgh in 1802. In 1805, Scott became financial backer and part-owner of James Ballantyne and Co. As such, the relationship was far from being a straightforward one of author/printer. It was financial and literary. In Life of Scott Lockhart records many instances of Ballantyne’s literary engagement with Scott’s proofs. Millgate, however, points out that it is unjust to forget “Scott’s ongoing involvement in the business side of the printing firm” (“Kelso” 49). The co-existence of these two men, the intermingling of artistic and economic interests, on both sides, has much to do with the successful production and reception of The Heart of Mid-Lothian and the Waverley novels in general. The first London publication notice was provided both by the ‘Ebers Library’ and again the bookseller William Sams, the official Longman listing appearing three days later. Summary: VOL. I: p. i half-title. p. ii advertisement. p. iii title-page. p. iv inscription. pp. 1-10 introduction. pp. 1-333 text. VOL. II: p. i half-title 'TALES OF MY LANDLORD, | SECOND SERIES.' p. ii inscription. p. iii title-page. p. iv blank verso. p. 1 title 'THE | HEART OF MID-LOTHIAN. | VOL. II.' p. 2 blank verso. pp. 3-322 text. p. 322 printer's imprint. VOL. III: p. i half-title 'TALES OF MY LANDLORD, | SECOND SERIES.' p. ii inscription. p. iii title-page. p. iv blank verso. p. 1 title 'THE | HEART OF MID-LOTHIAN. | VOL. III.' p. 2 blank verso. pp. 3-328. p. 328 printer's imprint. VOL. IV: p. i half-title 'TALES OF MY LANDLORD, | SECOND SERIES.' p. ii inscription. p. iii title-page. p. iv blank verso. p. 1 title 'THE | HEART OF MID-LOTHIAN. | VOL. IV.' p. 2 blank verso. pp. 3-375 text. p. 375 printer's imprint. PLOT SUMMARY: VOL. I Opens in Edinburgh, 1736. Condemned criminal Andrew Wilson helps his accomplice Robertson/George Staunton escape from the Tolbooth (prison, central Edinburgh) as they are on their way to execution. Already sympathetic to Wilson after this act, a crowd of onlookers is outraged when the soldier presiding over Wilson's hanging, Captain Porteous, treats him with great brutality. A protest follows and the situation quickly gets out of hand. Porteous fires into the crowd and kills several bystanders. Porteous is tried and condemned for murder. However, a reprieve of six weeks is issued at the last minute by Queen Anne in London. Led by Staunton (in disguise), a well-organized and calm group of avengers advances upon the Tolbooth (otherwise known as ‘The Heart of Midlothian’). Porteous is lynched according to plan, but the scene turns brutal. At the same time, Staunton tries to liberate his lover Effie Deans, who is awaiting trial for child-murder in the Tolbooth, but she refuses to follow him and remains imprisoned. VOL. II Seduced by Staunton, Effie concealed her condition. As she is unable to produce the child or to call a witness stating that the birth of the child was announced, Effie will be tried under the law as a child murderer. Effie’s sister Jeanie must appear in court to testify. If Jeanie lies and says that Effie told her about the baby then the execution will likely be stayed. If not, a death sentence is inevitable. This conflict between the word of God and the word of man, the tension between the Covenant as taught to Jeanie by her devout father David Deans and British law, is central to the tale. Jeanie tells the truth. Effie is sentenced to death. VOL. III Following Effie’s sentence, Jeanie travels to London, mostly on foot, to appeal to the Queen for a stay of execution. In the course of her journey, she meets Madge Wildfire (formerly Staunton’s lover) and her mother Meg Murdockson (who sold Effie’s son to a vagrant woman to revenge Staunton’s seduction of her daughter). In London, Jeanie is aided by Scottish friends, especially by the Duke of Argyle. As such, she secures an interview with the Queen and manages the stay of execution to save her sister. Madge dies a horrible death at the hands of intolerant English hooligans. VOL. IV Jeanie marries her lover, the Presbyterian minister Reuben Butler, who is reconciled with her father David. The Duke of Argyle engages the family on his own estate, where they live prosperously. Effie is exiled, but marries Staunton. They live abroad. Many years later, Staunton and Effie return to search for their lost child. The child is indeed alive, but has grown into an outlaw, living amongst outsiders, raiding and pillaging upon the lands of Argyle. The youth, known as the Whistler, and Staunton meet for the first time in uncertain circumstances. Staunton is killed, likely by his own son, at their first meeting. The son is confined upon the estate, but released by the well-meaning Jeanie, whereupon he then flees to America to join an Indian tribe. Jedidiah Cleishbotham (J.C.) is one of Scott's many authorial devices. Scott's first novel Waverley (1814) was published anonymously. Thereafter Scott's novels were credited to the 'Author of Waverley'. The Tales of My Landlord series, of which Old Mortality and The Black Dwarf (published together as the first series in 1816), was slightly different in that the supposed author was Jedidiah Cleishbotham, a fictitious character. All four series of Tales of My Landlord were later included in Scott's Magnum Opus edition of the Waverley novels (1829). Publishing History In Sir Walter Scott: A Bibliographical History 1796-1832, William B. Todd and Ann Bowden provide information directly relevant to the domestic and international publishing history of The Heart of Mid-Lothian in terms of both reprints and derivatives. Reprints France: Paris: Baudry, Barrois [and others], 1831. (Collection of Ancient and Modern British Novels and Romances); Paris: Didot and Galignani, 1821. (Collection of Modern English Authors). Germany: Publishing history: Berlin: Schlesinger, 1822; Leipzig: Wigand, 1831. (A Complete Edition of the Waverley Novels); Zwickau: Schumann, 1822. (Pocket Library of English Classics). United States: Publishing history: Boston: Parker, 1821-1832; Hartford: Goodrich, and Huntington and Hopkins, 1821; New York: Duyckinck, Gilley, Lockwood, and Bliss, 1820; New York: Van Winkle, 1818; Philadelphia: Carey and Son, 1818; Philadelphia: Crissy, 1826; Philadelphia: Dickinson, 1821. This is far from being a complete list. The online database OCLC Worldcat provides a more in-depth listing. Derivatives One of the more remarkable aspects of The Heart of Mid-Lothian is the massive attempt to cash in on its success by way of derivatives. The following list provides some consideration of the shift to drama, melodrama, choruses, airs, and chapbooks that took place immediately following initial publication in 1818, a shift that Scott himself was not averse to and actively participated in by leaking early copy to the dramatist Daniel Terry for adaptation. It is important to keep in mind that this list does not include operas and is not exhaustive, particularly so as it cannot recover the influence of the illegal domestic and offshore printing practices that abounded. A few examples Drama: London: Goulding, D’Almaine, Potter, 1819. The Overture and Whole of the Music in The Heart of Mid-Lothian; A Musical drama in three acts. (Daniel Terry); London: Stockdale, 1819; Dublin: The Booksellers, 1819; Edinburgh: Huie, 1822; London: Hodgson, 1822. The Heart of Mid-Lothian; or, The Lily of St. Leonard’s; London: Cumberland, 1830; Baltimore: Robinson, 1828. The Heart of Mid-Lothian: A Melo-Dramatic Romance, in Three Acts. (Drama by Thomas John Dibdin). Melodrama: London: Stodart, 1819. The Heart of Mid-Lothian; or, The Lily of St. Leonard’s: A Melo-Dramatic Romance, in Three Acts. (Melodrama by Thomas John Dibdin). Airs and Choruses: London: Macleish, 1819. Airs, Choruses, &c. &c. In the New Drama, (in Three Acts,) Called the Heart of Mid-Lothian. Chapbook: Edinburgh: Caw and Elder, 1818; Newcastle Upon Tyne: Mackenzie and Dent, 1819. The Heart of Mid-Lothian, or The Affecting History of Jeanie and Effie Deans; London: Bailey, 1823; London: The Company of Booksellers, 1822; London: Duncombe, 1820. Opera: German and French: Mainz : B. Schotts Söhnen, [1833?]. La prison d'Édimbourg : opéra comique en 3 actes by Michele Carafa. Italian: Milano: Gio. Ricordi, [1838]. La prigione d'Edimburgo : melodramma semiserio / poesia del Gaetano Rossi; musica del Federico Ricci; English: London: Mathias & Strickland, c1894. Jeanie Deans : a grand opera in four acts / ... written and arranged by Joseph Bennett on Sir Walter Scott's Heart of Midlothian ; music by Hamish McCunn ; vocal score. Author: MacCunn, Hamish, 1868-1916. Reception The ‘Author of Waverley’, widely considered to be the author of Tales of My Landlord as well, became something of a brand. Each new novel was demanded immediately by printers, publishers, and readers as soon as it appeared, or even before, by whatever means available. Accordingly, circulating libraries bought copies without delay, copies which were rarely if ever not in use throughout the nineteenth century. Although an overall success, the initial print run of 10,000 copies did not sell as quickly as the preceding novel Rob Roy for a number of reasons. To start, critical reaction was not unanimous. “Criticism centred on the fourth volume which was felt to protract the novel beyond its natural conclusion. Blackwood's and the British Review suggested that it had been tagged on with profit in mind. The Monthly Review argued that Effie’s transformation into Lady Staunton and Staunton's death at the hands were excessively improbable” (Walter Scott Digital Archive). There was also an election, it was summer, the fourth part was very long, and perhaps most importantly, a deal with the London publisher Longman was not concluded thus leaving Constable and Company as the sole publisher without a primary English partner. Regardless, the publication was a smashing success in Scotland and in Britain generally. It was also well-received abroad, particularly in America, where the arrival of every Waverley novel was a highly anticipated event, for both potential publishers and enthusiastic readers. The Heart of Mid-Lothian was reviewed by 23 periodicals. This represented a significant increase compared with the first three Waverley novels. From 1818 onward Scott is noticed in a wide range of periodicals. Despite the aforementioned criticism, reviewers praised the working-class heroine far more than other Scott heroes. In The Reception of Jane Austen and Walter Scott Annika Bautz writes: “Reviewers’ interest in Jeanie shows again that the more characters differ from what critics are used to, both in their own lives and in fiction, the more captivating the characters become – whether Highland or Lowland, romantic or commonplace” (36). Overall, in spite of general acceptance as an acknowledged canonical figure in the history of Western literature, Walter Scott does not figure prominently for most contemporary readers. A recent mild resurgence in academic interest still leaves Scott underappreciated in academia, particularly outside Britain. However, The Heart of Mid-Lothian is one of the few Waverley novels that continues to interest Scott scholars and others in the fields of Romanticism or English studies. “Many now consider The Heart of Midlothian to be the best of the Waverley novels” (Walter Scott Digital Archive). Gary Kelly English Fiction in the Romantic Period, Jane Millgate The Making of the Novelist, William St. Clair The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period, Andrew Lincoln Walter Scott and Modernity, and the 2004 Edinburgh Edition of The Heart of Mid-Lothian edited by David Hewitt and Alison Lumsden provide excellent accounts from a variety of angles. The Walter Scott Digital Archive and MLA Bibliography provide further means of locating contemporary assessments. Print Resources Alexander, J. H., David Hewitt, and International Conference on Sir Walter Scott (2nd : 1982 : University of Aberdeen). Scott and His Influence : The Papers of the Aberdeen Scott Conference, 1982. Aberdeen: Association for Scottish Literary Studies, 1983. Anderson, Carol. "The Power of Naming: Language, Identity and Betrayal in the Heart of Midlothian." Critical Essays on Sir Walter Scott: The Waverley Novels. Ed. Harry E. Shaw. New York: Hall, 1996. 182-193. Austin, Carolyn F. "Home and Nation in the Heart of Midlothian." SEL: Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 40.4 (2000): 621-34. Ballantyne & company. The History of the Ballantyne Press and its Connection with Sir Walter Scott, Bart. Edinburgh, etc: Printed at the Ballantyne press, 1871. Bautz, Annika. The Reception of Jane Austen and Walter Scott : A Comparative Longitudinal Study. London; New York: Continuum, 2007. Brough, William, and Walter Scott Sir. The Great Sensation Trial, Or, Circumstantial Effie-Deans Microform : A Burlesque Extravaganza. London: Office of the Dramatic Author's Society, 1863. Buchan, John. The Man and the Book: Sir Walter Scott,. London and Edinburgh, T. Nelson & sons: ltd, 1925. Chun, Seung-hei. "[Walter Scott's Historicism in the Heart of Midlothian]." The Journal of English Language and Literature 41.2 (1995): 359-75. Craig, David. "The Heart of Midlothian: Its Religious Basis." Essays in Criticism 8 (1958): 217-25. Criscuola, Margaret Movshin. "The Porteous Mob: Fact and Truth in the Heart of Midlothian." English Language Notes 22.1 (1984): 43-50. D'Arcy, Julian Meldon. "Roseneath: Scotland Or 'Scott-Land'? A Reappraisal of the Heart of Midlothian." Studies in Scottish Literature 32 (2001): 26-36. Davis, Jana. "Sir Walter Scott's the Heart of Midlothian and Scottish Common-Sense Morality." Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature 21.4 (1988): 55-63. Edgecombe, R. S. "Two Female Saviours in Nineteenth-Century Fiction: Jeanie Deans and Mary Barton." English Studies: A Journal of English Language and Literature 77.1 (1996): 45-58. Fisher, P. F. "Providence, Fate, and the Historical Imagination in Scott's the Heart of Midlothian." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 10.2 (1955): 99-114. Hannaford, Richard. "Dumbiedikes, Ratcliffe, and a Surprising Jeanie Deans: Comic Alternatives in the Heart of Mid-Lothian." Studies in the Novel 30.1 (1998): 1-19. Hewitt, David, and Alison Lumsden. Walter Scott/The Heart of Mid-Lothian. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh UP, 2004. Hewitt, David. "The Heart of Mid-Lothian and 'the People'." European Romantic Review 13.3 (2002): 299-309. Hyde, William J. "Jeanie Deans and the Queen: Appearance and Reality." Nineteenth-Century Fiction 28.1 (1973): 86-92. Kerr, James. "Scott's Fable of Regeneration: The Heart of Midlothian." ELH 53.4 (1986): 801-20. Kelly, Gary. English Fiction of the Romantic Period, 1789-1830. London; New York: Longman, 1989. Lincoln, Andrew. "Conciliation, Resistance and the Unspeakable in the Heart of Mid-Lothian." Philological Quarterly 79.1 (2000): 69-90. ---. Walter Scott and Modernity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2007. Lockhart, J. G. Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. Edinburgh : R. Cadell, 1837. Lukács, György. The Historical Novel. London: Merlin Press, 1962. Lurz, John. "Pro-Visional Reading: Seeing Walter Scott's the Heart of Mid-Lothian." Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory 19.3 (2008): 248-67. McCracken-Flesher, Caroline. "Narrating the (Gendered) Nation in Walter Scott's the Heart of Midlothian." Nineteenth-Century Contexts 24.3 (2002): 291-316. McLellan, Barbara Lindsay Holliday. "Pathways of the Heroines: A Comparative Study of Jeanie and Effie Deans, Emma Bovary and Tess Durbeyfield." Dissertation Abstracts International 56.6 (1995): 2228A-. Millgate, Jane. “Archibald Constable and the Problem of London: ‘Quite the connection we have been looking for’.” The Transactions of the Bibliographical Society 18:2 (June, 1996), pp. 110-23. ---. “From Kelso to Edinburgh: The Origins of the Scott-Ballantyne Partnership.” Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 92:1 (March 1998), pp. 33-51. ---. "Scott and the Law: The Heart of Midlothian." Rough Justice: Essays on Crime in Literature. Ed. M. L. Friedland. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991. 95-113. ---. Walter Scott: The Making of the Novelist. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987. ---. 'Walter Scott and the Management of Copyright' [The Edinburgh history of the book in Scotland, 1800-80]. In Bell, Bill (ed.), The Edinburgh history of the book in Scotland : vol. 3 : Ambition and Industry 1800-80 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), 212-20. Monk, Leland. "The Novel as Prison: Scott's the Heart of Midlothian." Novel: A Forum on Fiction 27.3 (1994): 287-303. Murphy, Peter. "Scott's Disappointments: Reading the Heart of Midlothian." Modern Philology: A Journal Devoted to Research in Medieval and Modern Literature 92.2 (1994): 179-98. Negrillo, Ana Díaz. "Jeanie Deans: The Heroine of the Waverley Novels." Grove: Working Papers on English Studies 14 (2007): 41-52. Newman, Beth. "The Heart of Midlothian and the Masculinization of Fiction." Criticism: A Quarterly for Literature and the Arts 36.4 (1994): 521-40. Pittock, Joan H. "The Heart of Midlothian: Scott as Artist?" Essays in Criticism 7 (1957): 477-9. Raleigh, John Henry,ed. The Heart of Midlothian. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1966. Rigney, Ann. "Portable Monuments: Literature, Cultural Memory, and the Case of Jeanie Deans." Poetics Today 25.2 (2004): 361-96. Secor, Marie. "Jeanie Deans and the Nature of True Eloquence." Rhetorical Traditions and British Romantic Literature. Ed. Don H. Bialostosky and Lawrence D. Needham. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1995. 250-263. Shaw, Harry E., ed. Critical Essays on Sir Walter Scott : The Waverley Novels. New York; London: G.K. Hall; Prentice Hall International, 1996. St. Clair, William. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period. Cambridge, U.K; New York: Cambridge UP, 2004. Sussman, Charlotte. "The Emptiness at the Heart of Midlothian: Nation, Narration, and Population." Eighteenth-Century Fiction 15.1 (2002): 103-26. Thompson, Jon. "Sir Walter Scott and Madge Wildfire: Strategies of Containment in the Heart of Midlothian." Literature and History 13.2 (1987): 188-99. Todd, William B. and Ann Bowden. Sir Walter Scott; A Bibliographical History 1796-1832. Delaware, U.S.: Oak Knoll Press, 1998. Walker, Alistair D. "The Tentative Romantic: An Aspect of the Heart of Midlothian." English Studies: A Journal of English Language and Literature 69.2 (1988): 146-57. Wallace, Miriam L. "Nationalism and the Scottish Subject: The Uneasy Marriage of London and Edinburgh in Sir Walter Scott's the Heart of Midlothian." History of European Ideas 16.1-3 (1993): 41-7. Ward, Ian. "The Jurisprudential Heart of Midlothian." Scottish Literary Journal 24.1 (1997): 25-39. Whitmore, Daniel. "Fagin, Effie Deans, and the Spectacle of the Courtroom." Dickens Quarterly 3.3 (1986): 132-4. Online Resources The Edinburgh Sir Walter Scott Club http://www.eswsc.com/ Walter Scott Digital Archive (University of Edinburgh) http://www.walterscott.lib.ed.ac.uk/home.html Online Books by Walter Scott http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Scott%2C%20Walter%2C%20Sir%2C%201771-1832 Walter Scott Research Centre (Aberdeen University) http://abdn.ac.uk/prospectus/pgrad/study/research.php?code=walter_scott British Fiction 1800-1829 http://www.british-fiction.cf.ac.uk/titleDetails.asp?title=1818A056 Oxford Dictionary of National Bibliography: Walter Scott http://www.oxforddnb.com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/view/article/24928?docPos=6 The Heart of Mid-Lothian at Project Gutenberg http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/6944